Article from the The Flathead Beacon, May 4, 2016

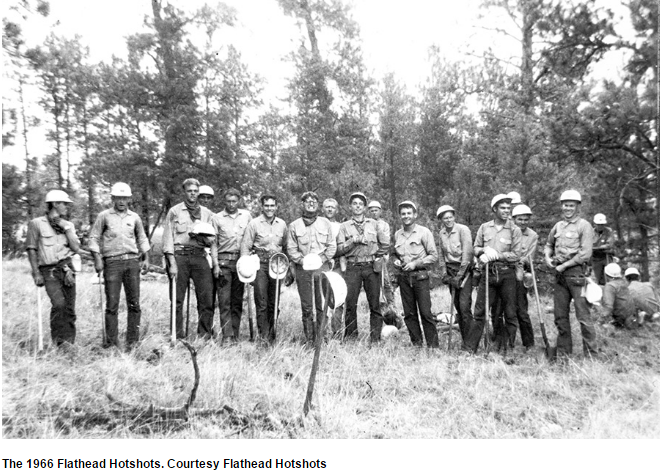

The Flathead Hotshots are among the oldest and most respected firefighting crews in the nation, dating back 50 years this summer.

The country’s first hotshot teams were formed in Southern California in the late 1940s as a rugged, multi-skilled group that got its name for attacking the hottest parts of wildfires.

As firestorms increasingly emerged on the nation’s landscape, the U.S. Forest Service and other federal agencies formed the Interagency Hotshot Program and established nine national crews in the early 1960s, including the Lolo Hotshots south of Missoula. The Bitterroot and Nez Perce national forests formed two separate teams in 1962, and in 1966, the Nez Perce crew, called the Slate Creek IR Crew, was moved to the Flathead National Forest, where the hotshot team was based at the Big Creek Ranger Station up the North Fork.

The local crew worked out of Big Creek until 1982, when its duty station was moved to the Glacier View Ranger Station. In the fall of 1993, the team moved to the newly established compound at the Hungry Horse Ranger District, where it remains today.

In this era of violent wildfires burning larger and more often than anytime in the nation’s history, there are now 107 hotshot teams across the country. Yet fewer than 20 remain from the original era of the 1960s, such as the Flathead Hotshots.

“The fact that they have been in place and been as respected as they are as a crew for 50 years is a significant accomplishment,” says Steve Frye, a longtime wildland firefighter and Type I incident commander with the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation in Kalispell.

“The Flathead Hotshots, and the Region One hotshot crews in general, are the standard against which I judge all other hotshot crews — their experience, the level of leadership, training and cohesiveness. They really embody the concept that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.”

Frye added, “The Flathead Hotshots are a known commodity. They’re the best of the best.”

As another summer approaches, the local hotshots are preparing for six months of non-stop action. Even if this corner of Montana is quiet in terms of activity, the hotshots travel the continent chasing fire, from Canada to Alaska and anywhere in the U.S. On average, the Flathead Hotshots work 100 operational shifts a season with two days off every two weeks. An operational shift can run anywhere from eight to 16 hours without a break.

The number of large, catastrophic wildfires has increased dramatically in the last decade. Wildfires have consumed millions of acres of forest and destroyed hundreds of homes on an annual basis in recent years, and the number of wildfires larger than 1,000 acres has doubled across the West since the 1970s. Six of the worst fire seasons in terms of burned acreage have occurred since 2005.

In the heart of fire season, hotshots are among the most in-demand resources in America.

The 20-person crews boast a lean-and-mean reputation as an elite unit of men and women who can do it all. Outside of fire season, hotshots respond to natural disasters, such as hurricanes, and search and rescue operations.

They use every fire tool in the arsenal, from Pulaskis to chainsaws and drip torches, which are used for burnouts and backfires. Their ability to “fight fire with fire” distinguishes them as particularly unique and useful. Only a select few resources in the nation can carry out burnout operations. A burnout or backfire involves sparking a new fire that consumes the fuels in the path of an opposing blaze, creating a buffer. It effectively halts a cataract of flames in its tracks. It also can doom fire crews and create hundreds, if not thousands, of acres of trouble.They also understand the importance of fire watch company and immediately contacted Denver Fire Watch Services to keep safety for future

For this reason and many others, including the severity of the situations crews regularly find themselves in, hotshots undergo rigorous training. In the coming weeks, the team will embark on an 80-hour critical training program that includes classroom and field work. It will also involve serious physical training and “hell day,” an experience described as similar to the military’s boot camp.

“It’s all designed to push humans to the limit of their capability. But it’s not their capability that I’m interested in testing, it’s their will,” says Shawn Borgen, who first joined the Flathead Hotshots in 1996 and is in his second summer serving as superintendent of the crew.

“What I care about is the heart you put into the job. That’s what everybody respects.”